Blog

Can AA truly cure addiction? – Dr William Flannery in the Sunday Business Post

- July 18, 2017

- Category: Blog College in the media External Affairs & Policy Featured Government Policy Of interest from media Stakeholders Uncategorized

Some addiction experts are now coming to the conclusion that Alcoholics Anonymous is a flawed enterprise. Are they right, asks Alex Meehan in the Sunday Business Post.

When a New York stock- broker named Bill Wilson met a surgeon named Dr Bob Smith in 1935, they were both hopeless alcoholics and desperate to find a way to turn their lives around.

At the time, it was common for alcoholism to be perceived as a moral failing, and a sign of weak character – medical science had little if any insight into the psychology of addiction. But out of that meeting came something extraordinary: the concept of the 12-step programme and a therapy that would spread across the world and be embraced by millions in the shape of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Today, AA has programmes in countless countries around the world and is embraced by people of all faiths and none. There’s just one problem – in the view of many experts, it simply doesn’t work.

In his 2014 book, The Sober Truth: Debunking the Bad Science Behind 12 Step Programs and the Rehab Industry, Dr Lance Dodes outlined his case against AA and the many organisations that have followed its methodology over the years.

To say it’s not evidence-based is an understatement,” he tells me over the phone from Los Angeles. “I became interested in AA because it is the predominant method of treatment for alcohol addiction in the US, and it’s really caused an incalculable degree of harm.”

Dodes has practised as a psychiatrist for nearly 40 years. He was assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, as well as director of the substance abuse treatment unit of Harvard’s McLean Hospital and director of the Alcoholism Treatment Unit at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital.

The problem isn’t that AA is useless,” he says. “It does help some people, but the number is low – only 5 to 8 per cent of the people who go to it. That’s a pretty widely accepted statistic now. The problem is that AA says it’s for everyone, and it’s clearly not.”

Ireland, according to recent research from the Health Research Board, has a huge issue with alcohol. But is AA really the answer to our issues with alcohol addiction?

Higher power

In the past, AA has said that its methods work for up to 75 per cent of people who go to meetings and attempt to follow the 12 steps closely.

However, these statistics are widely disputed, with many mental health professionals professing to be uneasy with the programme’s close links to religious faith and its insistence on the existence of a “higher power”. Six of the 12 steps that alcoholics are advised to follow reference God or a higher power.

In 2006, the Cochrane Collaboration, a healthcare research group, reviewed studies going back to the 1960s and found that “no experimental studies unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA” or 12-step programmes for reducing alcohol dependence.

“AA teaches that if its system doesn’t work for a person attending meetings and following the steps, the reason is because they didn’t try hard enough. What that means is that people go to it thinking that it’s the right treatment. So if it doesn’t work, instead of looking for better and more suitable treatments, they keep trying it,” says Dodes.

The biggest problem with AA, in his opinion, is that it tells people that “it works if you work it”.

That’s a horrible, dangerous and unethical thing to say, because it blames the patient for not getting well. Imagine if a drug manufacturer operated the same way – telling people it works if you work it. But AA takes exactly that line. The truth is that there are lots and lots of people who work very hard, yet it doesn’t work for them,” he says.

Dodes’s primary interest is in the psychology behind addictive behaviour, and almost all of his career has been focused on the subject. He had written several tomes on the subject before publishing A Sober Truth, with those previous books focusing on a new theory of addiction – that addiction has less to do with drugs and alcohol, and more to do with compulsive behaviour and the psychology that drives it.

“Where is a biological, psychological and a social component to addiction, you really need to hit all three areas”

Dr William Flannery is a consultant addictions psychiatrist and is vice-president of the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, and he has his own opinions on how addiction is best treated. To start with, he finds drawing a distinction between addiction being a disease and a psychological disorder to be unhelpful.

According to the World Health Organisation, addictions are listed as disorders. But I do lean towards the disease model as well. We tend to use the bio-psycho-social model – where there is a biological, psychological and a social component to addiction, and to be successful in dealing with it, you really need to hit all three areas,” he says.

“The mainstay of treating addictions is talking therapy or psycho-social interventions. They range from one-to-one addiction counselling with a cognitive behaviour basis, to residential or group work. There are also various medications that can support that intervention.”

Flannery is generally a supporter of the AA approach to treatment, although he acknowledges that there is a lack of evidence to support it.

“The research out there about it is relatively old and it doesn’t tell us an awful lot about it, but from clinical experience, I’ve seen that patients who do best of all tend to be those that attend fellowship meetings such as AA. That’s partly because it’s widespread and well established, so it’s not hard for people to find meetings, but it does have to be said that those people are a self-selecting sample,” he says.

“The people who are doing well will go, and the people who aren’t doing well won’t, so there is that. But I think some links to AA or directing people to AA is an essential part of any service. It’s not a treatment that we use – but it is a support for people who are otherwise receiving treatment.”

One of the values of AA, according to Flannery, is that it’s free and accessible. While there are lots of other services available for people with addiction issues, they can be expensive.

“It’s fine if you have insurance, but not if you don’t. If you have insurance, there’s quite a wide range of services available, both in-patient and out-patient in the vein of St John of God’s or St Pat’s – there is a wealth of services out there,” he said. “But if you don’t have insurance that will pay for it, then you’re dependent on the HSE. In that case, services are fragmentary at best and vary from place to place.”

Hitting rock bottom

One person for whom AA has been a success is John (not his real name), who is now in his 70s. He has not had a drink since 1974 and credits his success at staying away from alcohol to AA.

“Around my late teens, I started having problems with my mental health in the form of depression, anxiety and paranoia, and ended up three times in mental hospitals before the age of 22. At that time, in the late 1960s, there was a suggestion that I might be suffering from schizophrenia or be on the fringes of it, but I was also abusing alcohol and street drugs,” he says. “I ended up in London, penniless and living rough for two months in 1969. I abused a lot of drugs and managed to make it home, where I decided the drugs were getting me into too much trouble, and if I stuck to alcohol I’d be fine.”

However, John ended up in prison in 1970 as a result of his drinking, and it was while in jail that he first came across AA. “I took my last drink in February 1974 when I hit rock bottom, mentally, physically and spiritually,” he says. “I owe it all to that organisation, it turned my life around.”

Multi-faceted treatment

For Lance Dodes, the future for those whose experiences are not so positive, but who still need help with addiction, may lie in a multi-faceted treatment approach that could take the fellowship elements of AA – the group support which exists in many other organisations – and pair them with best practice in psychology.

But for that to happen, he believes the AA has to “get out of the way of progress”, and stop insisting that their way is the only way.

“I have no doubt that the people in AA are doing the best that they can, but they have no professional obligation to do the right thing for everyone. That’s not the case in medicine or psychiatry, where we do have an obligation to provide treatment for everyone who presents,” says Dodes.

Alcohol Addiction in Ireland

That Ireland has a problematic relationship with alcohol is news to nobody, but the degree to which we indulge is shocking. According to the Health Research Board (HRB), in 2016 the per capita rate of alcohol consumption in Ireland was 11.46 litres of pure alcohol per person, up from 10.93 litres in 2015.

When this is adjusted to account for the roughly 20 per cent of the population who don’t drink, it equates to 46 bottles of vodka, 130 bottles of wine or 498 pints of beer for every person in the country who drinks. In total, alcohol consumption in Ireland almost trebled over the four decades between 1960, when it was 4.9 litres per person, and 2001, when it hit 14.3 litres per person.

The social effects of this level of drinking on society are enormous. A report published last summer by the HRB said that the number of people discharged from hospital whose condition was totally attributable to alcohol rose by 82 per cent between 1995 and 2013, from 9,420 to 17,120 people.

It was also estimated at this time that around three Irish people a day died as a result of drinking alcohol. In addition, an estimated 5,315 people on the live register in November 2013 had lost their job due to alcohol use, and the estimated cost of alcohol-related absenteeism was €41,290,805 in 2013.

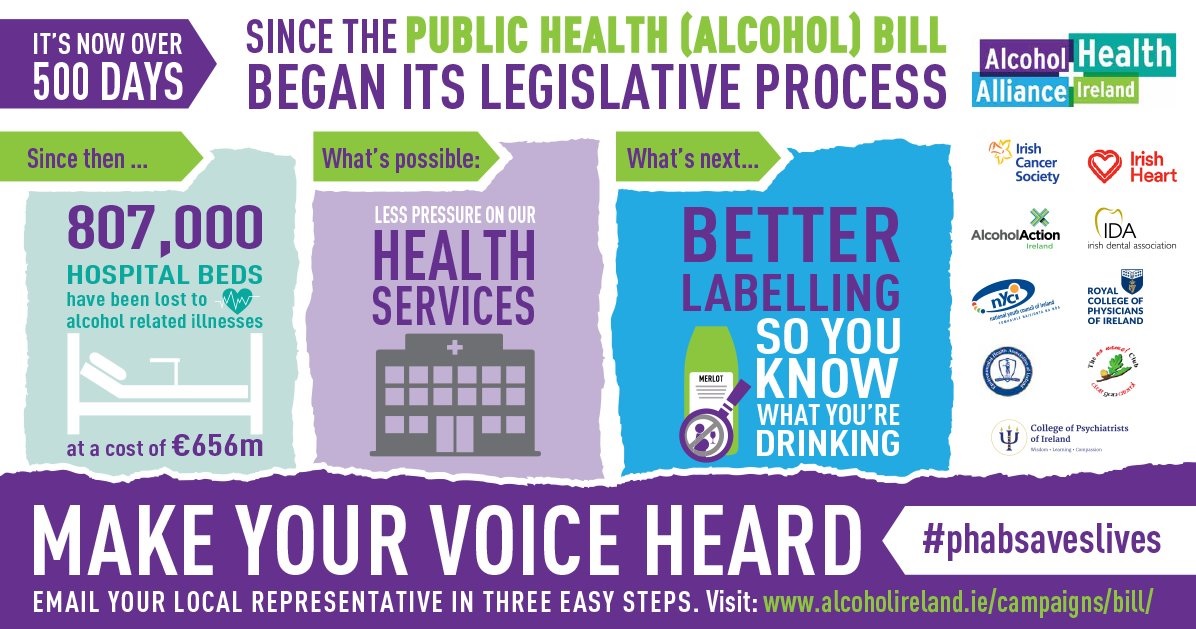

The College of Psychiatrists of Ireland is a member of the Alcohol Health Alliance, which was established by Alcohol Action Ireland and the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI), which aims to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. This new initiative supports the Public Health (Alcohol) Bill, which is a piece of legislation that has the potential to significantly reduce the harm caused by alcohol consumption in Ireland. To read more about this bill click here. To show your support for the bill please tweet using #PHABsaveslives